Week #16: I Get Along Without You Very Well (Except Sometimes) was written by Hoagy Carmichael in 1938. The lyrics were based on a poem by Jane Brown Thompson entitled Except Sometimes (reprinted below). The poem was published in 1924 in Life magazine. A friend of Carmichael’s saw the poem and gave it to Carmichael, who apparently put it in a drawer and forgot about it for a decade before re-discovering it and falling in love with its sentiment. Carmichael then painstakingly rewrote and added to the poem and crafted it into this song. The publishing of this song is actually a very interesting story in itself, which you can read here. Personally, I think these are some of the best crafted lyrics among the standards.

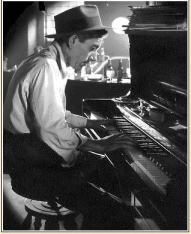

Chet Baker

The first recording of this song that I recall hearing is Chet Baker’s, whose voice seems designed for songs like this (listen here). Then, of course, there is Billie Holiday’s version, recorded in 1958, a year prior to her death (listen here). Holiday’s voice deteriorated in many ways in her later years, yet her ability to sing and interpret remained incredibly powerful, and I think that her later life recordings constitute some of her greatest work. Along all recordings of this song after 1940 treat it as a ballad, due to the ironic longing of the lyrics. However, when I listened to the earliest recordings of the song (like this one from Red Norvo), it was more of a dance tune. I certainly wouldn’t say the song works better this way, but I decided to try something a little more upbeat in my recording as well. I hope you enjoy it. Thanks for listening!

Except Sometimes – Jane Brown Thompson

I get along without you very well,

Of course I do.

Except the times a soft rain falls,

And dripping off the trees recalls

How you and I stood deep in mist

One day far in the woods, and kissed.

But now I get along without you — well,

Of course I do.I really have forgotten you, I boast,

Of course I have.

Except when somone sings a strain

Of song, then you are here again;

Or laughs a way which is the same

As yours; or when I hear your name.

I really have forgotten you — almost.

Of course I have.

Sinatra’s 1948 recording revived it (listen

Sinatra’s 1948 recording revived it (listen

Still, it wasn’t until 1955, nearly 30 years after Mack the Knife was written, that Louis Armstrong recorded a hugely popular version of the song (listen

Still, it wasn’t until 1955, nearly 30 years after Mack the Knife was written, that Louis Armstrong recorded a hugely popular version of the song (listen

The Charleston dance originated much earlier than the song, in the first years of the 1900’s. But it hit its peak of popularity in the mid-20’s; popular among flappers and in the speakeasies. The dance was considered quite provocative and immoral (along with the flappers’ infamous hair style and loose fitting clothes).*

The Charleston dance originated much earlier than the song, in the first years of the 1900’s. But it hit its peak of popularity in the mid-20’s; popular among flappers and in the speakeasies. The dance was considered quite provocative and immoral (along with the flappers’ infamous hair style and loose fitting clothes).*